Below is a paper I co-authored while a student at Stanford University. It explores the use of machine learning to help predict users’ news reading preferences. A link to download the PDF can be found at the bottom of the post.

Tag Archives: Technology

Automatic Insult Detection in Online Comments

Below is a research paper I co-authored while in graduate school at Stanford. A link to download the PDF can be found at the bottom of the post.

cs224u_report4Lição 6: Os blocos

Desenhar os blocos

- Igual que a gente tem uma função,

palgame.draw_circlepara desenhar uma círculo, a gentepalgame.draw_rectpara desenhar uma retângulo. - A gente sabe que precisa desenhar varias blocos – ou seja, a gente quer repetir os mesmo comando (draw_rect) varias vezes. Temos duas opções para repetir um comando: o for loop, e o while loop. Nesse caso qual deles é melhor?

- Lembra que caso a gente saiba quantas vezes a gente quer repetir uma coisa, melhor usar o for loop. Aqui, sim a gente sabe quantas vezes a gente quer repetir, porque sabemos quantos blocos precisamos.

- Vamos tentar desenhar varios blocos com o for loop então:

bloco_x = 5

bloco_y = 8

for i in range(10):

palgame.draw_rect(bloco_x, bloco_y, 20, 10)

- se a gente executar esses codigos, vai aparecer um bloco só. Por que? Por que mesmo que a gente desenhe 10 blocos, a gente nunca atualiza a posição ‘x’ e ‘y’ do bloco, então todos os blocos são desenhados no mesmo lugar!

- Ai, vamos atualizar a posição ‘x’ do bloco, para ter uma linha dos 10 blocos

bloco_x = 5

bloco_y = 8

LARGURA_DO_BLOCO = 20

ALTURA_DO_BLOCO = 10

for i in range(10):

palgame.draw_rect(bloco_x, bloco_y, LARGURA_DO_BLOCO, ALTURA_DO_BLOCO)

bloco_x = bloco_x + LARGURA_DO_BLOCO + 5

- Porem, a gente não quer uma linha só. Então a gente vai colocar esse for loop num outro for loop para ter um dobro for loop:

for i in range(LINHAS):

posicao_x = 5

for j in range(COLUNAS):

palgame.draw_rect(posicao_x, posicao_y, LARGURA_DO_BLOCO, ALTURA_DO_BLOCO)

posicao_x = posicao_x + LARGURA_DO_BLOCO + DISTANCA

posicao_y = posicao_y + ALTURA_DO_BLOCO + 5

Assim, o programa vai desenhar varias linhas, e para cada linha, vai criar varios blocos. O resultado é um grade de blocos.

Remover blocos

- Quando a bola bate o bloco, a gente quer que o bloco suma.

- Para realizar isso, a gente tem que apresentar o ideia de ‘state’. O ‘state’ é o estado atual do programa. Se vc guarda o ‘state’ de um aplicativo, vc pode parar o programa em qualquer momento, e reiniciar num outro momento.

- Então, nosso caso, a gente não quer simplesmente desenhar os blocos, a gente quer guardar a posição de cada bloco num lista, para lembrar quais blocos ainda existem e quais são destruidos.

Listas

- No Python, no mesmo jeito que a gente tem variaveis que são Numeros, Strings (palavras), e Booleans, a gente pode ter variaveis que são listas. Uma lista pode possuir varias outros tipos de variaveis. Por exemplo:

lista = [3, 1, 9, 2] print(lista) # vai imprimir 3, 1, 9, 2

- Para anexar uma coisa no final de uma lista, a gente usa o

append().

x = [3, 6, 1] x.append(2) print(x) # vai imprimir 3, 6, 1, 2

- Para remover uma coisa da lista, a gente usa o

remove()

x = [3, 9, 1, 4] x.remove(3) print(x) # vai imprimir 9, 1, 4

- Os elementos na lista não precisam ser numeros

x = ["hello", 9, 3, True] print(x) # vai imprimir "hello", 9, 3, True

- Agora, a gente vai guardar a posição x e a posição y para cada bloco num lista. Além disso, a gente vai guardar cada ‘bloco’ – ou seja, cada ‘x’ e ‘y’ – num outro, grande lista. Assim, a gente vai ter uma lista de listas que parece assim:

blocos = [ [0, 8], [5, 8], [10, 8], [15, 8] ]

- Nota aqui que cada elemento na lista é tambem uma lista pequena! Cada lista pequena, por exemplo [5, 8] representa um bloco.

- Então para criar tudos os blocos, a gente usa a mesmo dobra for loop, só que agora para cada bloco a gente cria uma lista de dois elementos (posição x e posição y) e adiciona esse elemento ao lista grande de blocos.

COLUNAS = 8

LINHAS = 5

DISTANCA = 10

LARGURA_DO_BLOCO = (LARGURA_DA_TELA / COLUNAS) - DISTANCA

ALTURA = 16

posicao_y = 0

blocos = []

for i in range(LINHAS):

posicao_x = 5

for j in range(COLUNAS):

b = [posicao_x, posicao_y]

blocos.append(b)

posicao_x = posicao_x + LARGURA_DO_BLOCO + DISTANCA

posicao_y = posicao_y + ALTURA + 5

- Agora para desenhar os blocos, é só pega cada bloco na lista, extrair o ‘x’ e ‘y’, e desenha:

for b in blocos:

palgame.draw_rect(b[0], b[1], LARGURA_DO_BLOCO, ALTURA)

Collisões

- Agora para checar se a bola bateu um bloco, a gente tem que checar, para cada bloco, se a posição da bola fica dentro do espaço do bloco. Caso essa seja verdade, a gente vai remover esse bloco da lista:

for a in blocos:

if (bola_x + raio) >= a[0] and (bola_x - raio) <= (a[0] + LARGURA_DO_BLOCO) and (bola_y + raio) >= a[1] and (bola_y - raio) <= (a[1] + ALTURA):

blocos.remove(a)

- Também nesse caso a gente quer que a bola volte, então a gente vai invertir a velocidade da bola:

for a in blocos:

if (bola_x + raio) >= a[0] and (bola_x - raio) <= (a[0] + LARGURA_DO_BLOCO) and (bola_y + raio) >= a[1] and (bola_y - raio) <= (a[1] + ALTURA):

blocos.remove(a)

velocidade_y = velocidade_y * -1

Lição 5: Movimento da bola

while loop infinito

- Lembra na ultima aula a gente conheceu o while loop, um jeito para repetir uma coisa varias vezes até uma condição seja falso.

- No caso de um jogo, a gente quer que a programa repita para sempre (na verdade, até o usario perca ou ganhe, mas para agora a gente pode pensar que é para sempre).

- Para efetuar esse “while loop infinito”, a gente precisa uma condição que nunca vai virar falso. Uns exemplos:

while 3 > 2:while "thiago" == "thiago"

- Esses condições sempre são verdade, então o while loop vai continuar para sempre. Mas para ter um programa mais legivel, o Python tem um tipo de variavel, se chama “boolean” para significar “Verdade” (True) ou “Falso” (False). Então eu posso escrever:

- while True:

- Qualquer coisa abaxio desta linha vai ser repetido para sempre por que

Truesempre é ‘verdade’

Aqui tem o link para o modelo do programa que a gente vai usar para criar esse jogo

Movimento da bola

x = 20

y = 30

raio = 5

cor = (255, 0, 0)

while True:

palgame.get_event()

palgame.clear_screen()

palgame.draw_circle(x, y, raio, cor)

palgame.draw_everything()

- Nota que dentro do while loop infinito, a gente está desenhando um círculo na posição (x, y) – nesse caso (20, 30) – e com um raio de 5 e cor vermelho.

- Lembra que os codigos que ficam dentro do while loop estão sendo repetidos – cada millissegundo.

Agora quero que a bola se mova. Como a gente pode fazer isso? Movimento é simplesmente uma mudança na posição de um objeto em relação do tempo. Então a gente vai atualizar a posição da bola dentro do while loop. Assim, a posição da bola vai mudar cada millisegundo – como esse acontece tão rapido, vai criar a sensação do movimento.

x = 20

y = 30

raio = 5

cor = (255, 0, 0)

while True:

palgame.get_event()

palgame.clear_screen()

x = x + 1 # atualizando a posição no eixo 'x'

y = y + 1 # atualizando a posição no eixo 'y'

palgame.draw_circle(x, y, raio, cor)

palgame.draw_everything()

- Se a gente quiser que a bola se mova mais rapido, é só aumentar a ‘velocidade’, ou seja, o tamanho da mudança:

x = x + 5

y = y + 5

- Como sempre, é melhor usar uma variavel para esse valor:

x = 20

y = 30

velocidade_x = 5

velocidade_y = 5

raio = 5

cor = (255, 0, 0)

while True:

palgame.get_event()

palgame.clear_screen()

x = x + velocidade_x # atualizando a posição no eixo 'x'

y = y + velocidade_y # atualizando a posição no eixo 'y'

palgame.draw_circle(x, y, raio, cor)

palgame.draw_everything()

Paredes

- Agora a gente tem a bola movendo, mas quando a bola chega a beira da tela, ela continua e some. Em vez disso, a gente quer que a bola reassalte nas paredes.

- Em termos do programa, a gente quer que a bola troque sentido.

- Primeiro, como a gente pode saber que a bola chegou na parede?

- É quando a posição da bola é igual (ou maior) do que a posição fixo da parede:

if x >= 700:

# Aqui a gente sabe que a bola bateu a parede direita

if x <= 0:

# Aqui a gente sabe que a bola bateu a parede izquerda

if y <= 0:

# Aqui a gente sabe que a bola bateu a parede superior

if y >= 400:

# Aqui a gente sabe que a bola bateu a parede inferior

- Segundo, como a gente consegue inverter o sentido da bola?

- Lembra que o movimento da bola é controlado pela velocidade, então para inverter o sentido do movimento, é só inverter a velocidade:

if x >= 700:

velocidade_x = velocidade_x * -1

if x <= 0:

velocidade_x = velocidade_x * -1

if y <= 0:

velocidade_y = velocidade_y * -1

if y > 400:

velocidade_y = velocidade_y * -1

Nota que a gente pode combinar essas linhas pq mesmo batendo parede izquerda ou parede direita, a gente vai inverter velocidade_x

if x >= 700 or x <= 0:

velocidade_x = velocidade_x * -1

if y <= 0 or y >= 400:

velocidade_y = velocidade_y * -1

Lição 4: while loop

while loop

- Na segunda aula, a gente aprendeu o ‘for loop’, um jeito para repetir os mesmos comandos varias vezes

- No caso do for loop, a gente tinha que saber exatamente quantas vezes a gente quer repetir uma coisa. Por exemplo:

import turtle

for i in range (4):

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(90)

Nesse exemplo, a gente sabe antecipadamente que a gente quer fazer o seguinte 4 vezes, nem mais nem menos.

- Porém, há situações onde o desenvolvedor nem sabe quantas vezes ele quer repetir uma coisa. Ele simplesmente sabe que ele quer repetir uma coisa até que uma condição seja cumprida.

numero = 1

while numero < 100:

numero = numero * 2

Aqui eu quero multiplicar um numero por 2 até que o numero seja maior do que 100. Eu não sei quantas vezes eu preciso fazer isso, só sei que quero fazer isso até o numero seja maior do que 100.

- As condições que a gente usa no while loop são iguais do que elas que a gente usa no if statement. Então a gente pode usar as conjunções ‘<‘, ‘>’, ‘<=’, ‘>=’, ‘==’, ‘!=’

- Agora, vamos fazer um exemplo mais complicado com o while loop. A gente vai implementar o Conjectura de Collatz:

Esta conjectura aplica-se a qualquer número natural, e diz-nos para, se este número for par, o dividir por 2 (/2), e se for impar, para multiplicar por 3 e adicionar 1 (*3+1). Desta forma, por exemplo, se a sequência iniciar com o número 5 ter-se-á: 5; 16; 8; 4; 2; 1. A conjectura apresenta uma regra dizendo que, qualquer número natural, quando aplicado a esta regra, eventualmente sempre chegará a 4, que se converte em 2 e termina em 1.

numero = 18

while numero != 1:

if numero % 2 == 0:

numero = numero / 2

else:

numero = (numero * 3) + 1

print(numero)

- Enquanto que o numero não seja 1, a gente vai fazer o seguinte: se o numero for par, divide por 2, se o numero não for par, multiplica por 3 e adiciona 1.

Lição 3: if/else statements

Na última aula a gente aprendeu alguns ferramentos que nos deixa escrever codigos com mais facilidade: variaveis (para guardar, reutilizar e modificar valores) o ‘for loop’ (para repetir uma coisa varias vezes) e o ‘function’ (para organizar um serie de instruções num lugar). Agora a gente vai aprender outros e no fim dessa aula, vcs terão tudos os ferramentos que precisam para esse curso e a gente pode começar criar programas mais complexos.

if statement

- Até agora, o computador sempre executava todas as instruções que a gente escreveu. Porem, para programas e aplicativos mais complexos, a gente não quer sempre executar tudos os codigos.

- Em vez disso, a gente quer controlar o fluxo do programa e executar partes determinidos do programa, dependendo de uma condição. Por exemplo, num site como Facebook, se um usuario tem permissões para ver um post, o Facebook vai mostrar, mas, se ele não tem, não vai aparecer o post.

- Para fazer isso, a gente escreve um ‘if’, depois uma condição, e em baixo, os codigos que a gente quer executar caso essa condição seja verdade:

x = 7

if x > 5:

print("ola")

- Nessa caso, o que vai acontecer? O computador guarda o valor ‘7’ na variavel ‘x’. E depois, ele vai checar: se o variavel ‘x’ (ou seja, 7) for maior do que 5. Como que 7 sim é maior do que 5, o computador vai executar os codigos dentro do ‘if statement’ e vai imprimir “ola”

- Agora vamos modificar o exemplo:

x = 3

if x > 5:

print ("ola")

- Agora, o valor do ‘x’ não é maior do que 5, então o computador não vai imprimir nada

- Nota que a gente usa o simbilo ‘>’ para significar “maior do que”. Além disso, existem outros simbilos:

- ‘<‘ (menor do que)

- ‘<=’ (menor do que ou igual a)

- ‘>=’ (maior do que ou igual a)

- ‘==’ (igual a)

- ‘!=’ (não é igual a)

- Esses simbilos de comparação funcionam com palavras tambem:

nome = "thiago"

if nome == "thiago":

print("bom dia")

Esse programa vai imprimir “bom dia” por que o variavel ‘nome’ é igaul a “thiago”. Nota: no contexto das palavras (‘strings’) o simbilo ‘>’ significa ‘vem primeiro alfabeticamente’. Por exemplo:

nome = "pedro"

if nome > "thiago":

print ("bom dia")

Nesse caso, o computador não vai imprimir “bom dia” por que a palavra “thiago” vem depois do que “pedro” alfabeticamente, ou seja, “pedro” é maior do que “thiago”.

Combinar condições

- É possivel combinar varias condições num ‘if statement’. Há duas conjunções: ‘and‘ (e) e ‘or‘ (ou).

x = 5 y = 9 if x > 4 and y > 12:

Nesse exemplo, o computador não vai imprimir nada, por que mesmo que o ‘x’ seja maior do que 4, o ‘y’ não é maior do que 12. Como que a gente tem a conjução ‘and’ entres as duas condições, as duas tem que ser verdade para executar os codigos em baixo.

nacionalidade = "brasileiro"

idade = 35

if nacionalidade == "brasileiro" and idade >= 18:

print ("pode votar")

Nesse exemplo, as duas condições são verdade, ou seja, ‘nacionalidade’ é igual a “brasileiro” e idade e maior do que (ou igaul a) 18, então o computador vai imprimir “pode votar”.

idade = 70

if idade < 18 or idade > 65:

preco = 15

print ("preco é", preco)

Aqui, a gente usa a conjução ‘or’. Então só uma das duas condições tem que ser verdade. Nesse caso a primeira condição (idade < 18) não é verdade, mais a segunda (idade > 65) é verdade, então os codigos dentro do if statement vai ser executados.

- Lembra que os espaços são importantes! Qualquer codigos que voçê quer colocar ‘dentro’ do if statement tem que começar com um ‘tab’

else

- Para ter ainda mais controle no fluxo do programa, a gente pode usar o ‘else statement’. ‘else’ significa ‘se não’ e o ‘else statement’ é usado conjunto com o ‘if statement’. Por exemplo

def ingresso (idade):

if idade < 18 or idade > 65:

print "preco meia"

else:

print "preco inteiro"

ingresso(45)

Aqui, caso a condição seja verdade, vai imprimir “preco meia”, mas caso não, vai imprimir preco inteiro”. Como que idade é 45 (eu passo o valor como um parâmetro no function) Não esqueça os dois pontinhos depois do ‘else’!

Vamos combinar o if statement e o for loop para escrever um function que pode detectar se um numero for primo ou não.

- Para saber se um numero for primo, a gente tem que checar todos os numeros desde 2 até o numero, e ver se un deles divide o numero sem sobrar nada.

- A gente usa o ‘for loop’ para anda por todos os numeros

- A gente usa o ‘if statement’ para checar a condição de cada numero.

- Assim que a gente ache um numero que divide o numero original sem sobrar nada, a gente pode terminar, pois não se precisa checar os outros. Aí nesse caso a gente imprime “numero não é primo” e ‘return’ para sair do function.

- Caso a gente verifique que nenhum dos numeros divide o numero original (ou seja, o for loop termina) a gente pode dizer nesse momento que o numero original realmente é primo.

def isprime (num):

for i in range (2, num):

if num % i == 0:

print ("numero não é primo")

return

print("numero é primo")

isprime(13)

Lição 2: Mais exercícios com o Turtle

Mais comandos do Turtle

turtle.penup() # Levantar a 'caneta' do turtle. Assim vc pode mudar o turtle sem desenhar nada turtle.pendown() # Abaixar a 'caneta' do turtle, para começar desenhar turtle.begin_fill() # Usa esse comando antes de começar desenhar uma forma, para encher a forma com cor turtle.end_fill() # Usa esse comando depois de desenhar uma forma, para encher a forma com cor turtle.goto(x, y) # Ir direito para uma posição. Os parâmetros x e y representam os coordenadas da posição onde vc quer que o turtle vá. turtle.circle(radius) # Desenhar um círculo

Um exemplo

Aqui tem um exemplo que usa uma função e usa os comandos que a gente aprendeu

import turtle

turtle.shape("turtle")

# draw a square

def desenha_triangulo(cor):

turtle.color(cor)

turtle.begin_fill()

turtle.left(45)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(136)

turtle.forward(140)

turtle.end_fill()

turtle.left(100)

desenha_triangulo("blue")

turtle.left(15)

desenha_triangulo("green")

turtle.left(15)

desenha_triangulo("red")

turtle.left(15)

desenha_triangulo("yellow")

turtle.left(15)

desenha_triangulo("pink")

turtle.left(15)

turtle.color('black')

turtle.left(180)

turtle.forward(180)

turtle.mainloop()

Lição 1: Introdução à programação

O que é programação:

- Idioma para falar com o computador

- Linguagem imperativa: voçê está mandando ordens para o computador

- A gramática é muito estrita: se voçê cometer um erro, o computador não vai entender

Python

- Python é a linguagem que a gente vai usar nesse curso

- É uma linguagem bem popular no mundo, usado no Facebook, Google, NASA, e jogos como Civilization IV

Turtle

- Turtle é um pacote do Python que é usado para desenhar coisas na tela

- O turtle tem varios comandos, incluindo:

turtle.left()turtle.right()turtle.forward() - Pode combinar esses comandos para desenhar formas, por exemplo:import turtle

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(90)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(90)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(90)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.mainloop()Erros comuns:

- Falta parêntese:

turtle.forward(10 - Error ortográfico:

turtle.farward(100)

- Falta parêntese:

Variáveis

- A gente usa variáveis para guardar informações na memoria

- Com isso, nossos programas ficam mais flexiveis. Eu posso mudar o valor do variavel num lugar, e ele muda no programa inteiro, por exemplo

import turtle tamanho = 200 angulo = 90 turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.mainloop()

- É importante usar nomes relevantes com as variaveis, tipo ‘tamanho’ em vez de ‘x’

- A gente pode deixa o computador calcular o valor de uma variavel:

import turtle tamanho = 200 lados = 4 angulo = 360 / lados turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.right(angulo) turtle.forward(tamanho) turtle.mainloop()

for loop

- Um princípio muito importante na programação é D.R.Y (Don’t Repeat Yourself) – Não Se Repita

- Nesse programa encima, a gente tá repetindo a linha

turtle.forward(tamanho)eturtle.right(angulo) - Para não ficar repetindo, a gente pode usar o for loop. O for loop diz para o computador: “Repita o seguinte X vezes”. Por exemplo

for i in range(4):

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(90)

- Esse significa: Repita 4 vezes os duas linhas em baixo

- Agora o programa encima vira:

import turtle

tamanho = 100

lados = 4

angulo = 360 / lados

for i in range(lados):

turtle.forward(tamanho)

turtle.right(angulo)

turtle.mainloop()

- Agora a gente pode simplesmente modificar o ‘tamanho’ e o ‘lados’ para criar várias formas diferentes

Functions

- Se a gente quisesse desenhar várias formas na mesma tela, a gente teria que copiar e colar esse for loop e cada vez mudar o valor dos variaveis (tamanho, lados).

- Como a gente nunca quer se repetir assim, a gente vai usar uma function (função)

- A function está escrito assim (Preste atenção à sintaxe):

def desenhar_forma (lados, tamanho):

angulo = 360 / lados

for i in range(lados):

turtle.forward(tamanho)

turtle.right(angulo)

- Esses codigos aqui é só a declaração da function. Ainda a gente não usou o function mesmo. Para usar, a gente tem que passar os parâmetros no mesmo ordem que eles são declarados:

import turtle

def draw_shape (lados, tamanho):

angulo = 360 / lados

for i in range(lados):

turtle.forward(tamanho)

turtle.right(angulo)

draw_shape(6, 100)

turtle.mainloop()

- O uso da function tem que acontecer depois do que a declaração da function

- No Python os espaços são importantes. Todas as linhas que estão dentro do function tem começar com um ‘tab’

- Um function pode aceitar qualquer numero de parâmetros. Há outro comando no turtle para mudar o cor. Então a gente vai adicionar mais um parâmetro ao function, se chama ‘cor’. Assim a gente pode criar varias formas com cores diferentes.

import turtle

def draw_shape (lados, tamanho, cor):

turtle.color(cor)

angulo = 360 / lados

for i in range(lados):

turtle.forward(tamanho)

turtle.right(angulo)

draw_shape(6, 100, "green")

draw_shape(3, 200, "red")

turtle.mainloop()

- Lembra que os nomes dos variaveis não são importantes para o computador (eu poderia escolher nomes tipo “x”, “y”, “z” em vez de “lados”, “tamanho”, “angulo”, mais, mesmo assim, é importante escolher nomes relevantes para que outras pessoas possam entender a seu programa.

Mais comandos do turtle

- Existem muitos mais comandos para o turtle. Para ver uma lista completa desses comandos, visita essa pagina aqui

Qualquer duvida, escreva um comentário aqui em baixo e eu vou responder 🙂 Obrigado!

Fantastic Bugs And Where To Find Them

Last Friday we encountered a bug in our codebase whose origin was of such a peculiar nature, and whose eventual resolution proved so instructive, that I thought I would record it here.

First, some brief background. EndlessOS is built for two different computer architectures: x86 and ARM. With a few notable exceptions, personal computers generally run x86, while tablets and smartphones run ARM. In an effort to bring down the cost of PCs (ARM chips tend to be cheaper) Endless has released a desktop computer running ARM. Since the chipsets are designed differently, compilation – that is, the process by which we translate source code to machine code – must happen separately for each architecture. Our OS, with all its accompanying apps and tools, must be built twice, and, of course, tested twice. However, application code, living as it does in the cushy land of user space, usually does not exhibit different behaviour when running on ARM versus running on x86. In fact, only if you are doing low-level processor instructions, such as bit manipulation, should you even care what chip architecture you are running on. It was, therefore, to our surprise (and, indeed, horror) when we discovered, late in a release cycle, that a number of our apps had been shown to work on the x86 machines, but not on the ARM machines. The QA team reported that upon opening one of these problematic apps, the user would never be able to access a subset page. Without going into too much detail, suffice it to say that the data in our apps is organized into ‘sets’ and ‘subsets’; clicking on the title of a subset ought to take you to the subset page.

Our apps are built with a homegrown framework we have at Endless called the Knowledge Library. The framework provides a number of components, or ‘Modules’, which you can use to rapidly build complex, data-driven applications. Apps are built in Facebook’s Flux paradigm, complete with a dispatcher, history store, and of course, views in the form of GtkWidgets. I knew (because we had built it) that the module responsible for transitioning between pages in an app was the Pager. Examining the Pager code, we found the line responsible for displaying the subset page:

if (SetMap.get_parent_set(item.model) && this._subset_page) {

this._show_page_if_present(this._subset_page);

}

If the subset page wasn’t showing up, it meant that one of the two expressions in the if condition was evaluating to false when it shouldn’t do. The second condition this._subset_page simply checks to see if you have a subset page at all in your app, which I knew we did. The first condition queries the SetMap – an in-memory graph which maps relationships between set models in the database – and asks if the parent set of the model in question is defined. In essence, this is equivalent to asking if model has a parent set – if it does, then we know that the model is a subset, and that therefore it is appropriate to show the subset page. We suspected, then, that something was up with the contents of this SetMap – specifically, we guessed, based on knowing how SetMap was written, that it had no data in it at all, and was just mindlessly returning null for any and all set queries we gave it.

We decided to take a look at where SetMap was getting its data from, and found this function:

initialize_set_map: function (cb) {

Eknc.Engine.get_default().query(Eknc.QueryObject.new_from_props({

limit: -1,

tags_match_all: ['EknSetObject'],

}), null, (engine, res) => {

let results;

try {

results = engine.query_finish(res);

} catch (e) {

logError(e, 'Failed to load sets from database');

return;

}

SetMap.init_map_with_models(results.models);

this._window.make_ready(cb);

});

}

The relevant context here is that the Engine retrieves data from our database according to the parameters of the query it is given. The query takes the form of a JSON object, and, in this case, is simply:

{

limit: -1,

tags_match_all: [‘EknSetObject’],

}

What we’re saying here is fetch me content tagged as ‘EknSetObject’, and don’t impose a limit. Now, if our hypothesis was correct, and the SetMap was empty, that meant that this query was returning nothing. However, we knew that we were seeing sets on the home page, and the query which returned those sets was remarkably similar:

{

limit: limit,

tags_match_all: ['EknSetObject'],

sort: Eknc.QueryObjectSort.SEQUENCE_NUMBER,

}

Both queries were asking for sets, but one was getting some and the other was getting none. What was different between them? Well, one difference we can see here is that the home page query requests its results to be sorted by the SEQUENCE_NUMBER key. Our Xapian backend database allows for sorting by predefined keys, and the SEQUENCE_NUMBER key describes the order in which models were added to the database. Having the results in that order is important when showing them on the home page, but in the case of a SetMap, where data isn’t going to be arranged linearly anyway, sorting is obviously irrelevant, so no sort field is included. In any case, whether data is sorted or not shouldn’t affect the quantity of said data that is returned, so we dismissed that as being the source of the problem.

What about that limit field though? Limits certainly do affect the quantity of things returned, and that -1 numeral seemed particularly suspect. I knew we had been using -1 as a special value to indicate ‘no limit’, but couldn’t quite recall how that worked. Just as a test, we changed the limit to a positive value, 10, and ran the app again. The bug was gone! The limit field was indeed the culprit, but our investigation had now only just begun. We certainly couldn’t leave this value at 10 – remember we wanted all sets returned, not just 10. Furthermore, this discovery seemed only to raise more questions: we had been using -1 to denote ‘no limit’ for many releases now, why were we only seeing that it was problematic now? If -1 was a problem for the query to handle, why was it not throwing an error, why instead return no results? And, perhaps most troublingly still, why were we only seeing this bug on the ARM architecture machines?

We dug more into the use of this limit field. Along with the rest of the query, the limit field eventually gets serialized into a JSON string and sent over an HTTP bridge to the local Xapian database server. Once on the server, which, unlike the app, is written in C, it gets parsed with the following line:

limit = (guint) g_ascii_strtod (str, NULL);

Here we were parsing the limit string as a double (the g_ascii_strtod() function converts strings to doubles) and then casting that double as an unsigned integer. Several things seemed awry at first glance: why were we parsing this limit field as a double, when doubles are meant only for storing floating point numbers? And, having parsed it as a double, why then cast it as an unsigned integer? Moreover, if it is meant to be an unsigned integer, how is -1 a valid input?

We pulled this line of code out into its own source file, ran it to see what happens when str is -1:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <glib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

int

main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

unsigned int limit = g_ascii_strtod ("-1", NULL);

fprintf (stderr, "limit := %u\n", limit);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Running on my intel machine this program printed out 4294967296, more commonly known as 232 – the maximum value expressible in a 32 bit integer. Aha! So here is where the -1 made good on its promise to be a ‘special value’ for fetching all sets. By casting it from a double to an unsigned int, we were exploiting the Two’s Complement method of storing integers to ‘transform’ the same binary number (in this case, 32 consecutive 1s) from a ‘-1’ to MAX_UINT. Setting the limit to be such a large value was effectively the same as saying ‘impose no limit’, and that is how we would get all sets returned.

We ran the same code snippet on ARM, and lo and behold, it printed out 0. We knew now that it was this line suffering from architecture dependent behaviour. But why? Why didn’t the ARM machine also exhibit the integer underflow trick? It turns out that, in the C programming language, underflowing an unsigned integer, far from being a clever trick, is in fact undefined behaviour. I had always vaguely been aware of this fact, but had not, until last week, quite appreciated the import of what that term carries. What I had understood about integer underflow, and other undefined behaviours, was that they were inadvisable, bad practice, perhaps even that they would trigger an error in certain cases. The truth is much more sinister than that, for the C spec is written not so much for you, the C programmer, as it is for the compiler. How operations behave and what constitutes valid syntax are built into the compiler. What then, does the C spec say about ‘undefined behaviour’:

Anything at all can happen; the Standard imposes no requirements. The program may fail to compile, or it may execute incorrectly (either crashing or silently generating incorrect results), or it may fortuitously do exactly what the programmer intended.

This blog post by a CS professor at the University of Utah provides an excellent overview of undefined behaviour in C and C++, but the bottom line is that once you invoke undefined behaviour, all bets are off: the entire program becomes meaningless. As long as it adheres to the explicit rules in the spec, compilers have enormous freedom. We violated those rules the moment we included an integer underflow. At that point the compiler could do whatever it pleases and still claim to be a valid C compiler. It could have refused to compile; it could have compiled and then promptly crashed; it could have compiled and then printed out the complete works of Charles Dickens to stdout. All of these are valid executions of the program because the program has now lost all meaning.

One might be tempted to think: ‘but surely only that single line was invalid. Even if it does do something bizarre when it reaches that line, shouldn’t the rest of the code up to that point function normally?’ This objection (which I myself raised) has both a theoretical and a practical answer. Theoretically, the answer is simply no that’s not how computer languages work – once you include undefined behaviour, the whole program is said to be meaningless. Furthermore, practically speaking, the notion of ‘reaching that line’ itself betrays a misunderstanding of how the compiler works: a compiler is at liberty to rearrange lines of code (which it does indeed do to optimize performance) provided such rearrangements will not have observable side effects on the execution of the program. Of course, a real world compiler probably won’t rearrange things such that that integer underflow line screws up the rest of the program, just as a real world compiler probably won’t print out the complete works of Charles Dickens when you try to divide by zero, but the point is that you can’t assume it won’t do those things, and there are lots of things it could do that lie in between that and normal execution. It could, for example, when it sees an undefined integer operation, choose to assign a zero value to the unsigned int. This is what apparently did happen on our ARM machines, and the reason why might have something to do with the ARM processor’s ability to store memory in both big-endian and little-endian format. In any case, when we consider the infinite domain of options that our illegitimate operation gave the compiler license for, returning zero now actually seems not unreasonable.

As is often the case, once we understood the problem, the patch itself was quite simple. Given that we were already late into the release cycle, the aim was to keep the diff on this patch small, so we simply added a check for the negative value

/* str may contain a negative value to mean "all matching results"; since

* casting a negative floating point value into an unsigned integer is

* undefined behavior, we need to perform some level of validation first

*/

{

double val = g_ascii_strtod (str, NULL);

/* Allow negative values to mean "all results" */

if (val < 0)

limit = G_MAXUINT;

else

limit = CLAMP (val, 0, G_MAXUINT);

}

This will ensure that the limit is never cast directly from a negative value to an unsigned int, and that its value always lives between 0 and MAX_UINT.

As any programmer will tell you, all intense debugging sessions always end with the desperate phrase, “but how did this ever work?”. The same was true for us, and what still bothered me was why we had never seen this error before, since that xapian-bridge code hadn’t been changed for several release cycles now. What had changed this time round was that the part of the codebase that actually handled these queries client-side had recently been ported from JavaScript to C. Grepping through that code base for any sign of the ‘limit’ field, we came across this line:

g_autofree gchar *limit_string = g_strdup_printf ("%d", limit);

The limit field had always had a GObject type of unsigned int, yet here we were treating it as a signed int. Back when this codebase was in JavaScript this line didn’t even exist, because why explicitly convert each property in an object to a string when we can just call JSON.stringify() directly? In C that serialization had to be done manually, and in doing so we mischaracterized an unsigned integer as a signed one. That’s why -1 was even getting sent to the xapian server in the first place – it never happened under Javascript because Javascript isn’t as low-level as C and hence never needed to ask us whether this was a signed integer or not – it ‘just knew’.

Patching this code up was a mere one character change (switch %d to %u ). Last, but not least we fixed the original query to request GLib.MAXUINT32 as its limit. Even though our server now gracefully handled the -1 value, it had always been bad practice to rely upon it. The fact that when I first delved into the code I found that line confusing seemed justification enough to clean it up.

So that was it: three separate bugs, working in tandem to produce this baffling, processor dependent result. I found the entire saga illuminating not only as regards to computer architecture but to the power of paired – or in this case quartet – programming. Each step along the way went faster because someone on our team had domain-specific knowledge that could be shared with the rest of the group. Here’s to more collaborative coding!

Dual problems in dual boot

Background

At Endless we distribute an installer that enables users to run both our own OS and Windows side by side, in a setup commonly known as dual-boot. Dual-boot allows users to try out our OS on their own hardware, without giving up the Windows system with which they are familiar or which they need to retain in order to run some Microsoft applications. A dual-boot enabled computer will, after powering on, display a simple menu screen, at which point the user can select which OS to run.

A grub menu screen showing two boot options: Endless OS and Windows

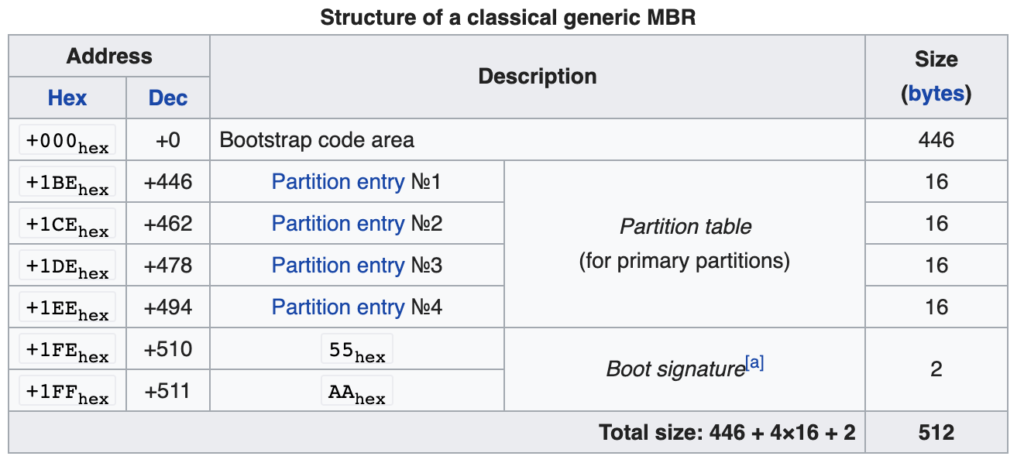

Most dual-boot installations work by overwriting the bootloader. You can think of the bootloader as the prima causa of all the software running on your computer. Every other piece of software that gets run (including the OS itself) must be loaded and executed by some other piece of software. The chain of causation stops at the bootloader, our unmoved mover. It sits right at the beginning of a hard disk, in the boot sector, and our hardware is physically configured to run whatever binary code is in that boot sector on startup.

What the Endless installer does is write into that boot sector a program called GRUB, the GRand Unified Bootloader, which, as you might guess from its grandiose title, is a powerful and flexible tool which coalesces into one program the ability to boot a variety of free operating systems, including Endless OS. Of course, one of the operating systems it does not know how to boot is Windows, so to get into Windows we use a process called chainloading. Before we write GRUB into the boot sector, we first copy out what was already there – namely, the Windows bootloader – and save it on the Windows partition. When a user chooses to boot into Windows, GRUB hands over control to the pre-saved Windows bootloader (this is the part known as chainloading) and the Windows boot sequence can begin.

Immediately after the boot sector usually comes the partition table, where information about the size and location of each of the disk’s partitions is stored. Most systems have four partitions, though more advanced ones can have as many as 16.

The layout of a disk drive, showing the boot record at the start.

Unlike some other Linux distros, such as Ubuntu, Endless does not create a separate partition on which to place its OS image. Rather, we stick the image into the C: drive of Windows itself, extending it to provide adequate space for the OS to work with, and hiding it with ACLs so that the user does not accidentally delete it while back on Windows! In fact, what we put in C: is an entire endless directory, which contains the endless.img image file, as well as a GRUB subdirectory with the grub.cfg file required to complete GRUB’s boot process. To identify the C: drive, GRUB looks for that partition which has the \endless\endless.img file on it. Once the partition is found, it can retrieve the grub.cfg file and complete the boot process. To boot into Endless, we launch the kernel, passing it these extra parameters:

endless.image.device=[id for partition holding endless.img] endless.image.path=/endless/endless.img

The disk layout on a computer with Ubuntu and Windows in dual boot.

The disk layout of a computer running EndlessOS and Windows in dual-boot.

As one might have surmised, because we are modifying the part of your computer that actually boots the rest of the OS, the stakes are rather high. In contrast to a bug in application code, which might – at worst – crash the application but leave the rest of your system intact, a bug here could render your entire computer unbootable. You could turn it on, but instead of an OS you would just get a dreary GRUB error screen. That is exactly what happened to a user of ours here in Brazil.

The Problem

A user reported that he had completed the installation process, but, upon reboot, had hit a black screen with a cryptic GRUB error message.

This error screen appeared after a user installed Endless and rebooted.

By examining the log file of another computer which had hit the same problem, we were able to figure out what went wrong. What appears to have happened is the following: our user completed the installation process successfully, but then, before exiting the installer, he closed his laptop lid, which puts the computer ‘to sleep’, or, more technically, tells Windows to broadcast a PBT_APMSUSPEND event signal to currently running applications. Closing the laptop was of course a perfectly reasonable thing to do, but due to a bug in our installer code, this signal caused the installer application to move into an error state, and when our user reopened his laptop lid later in the day, he saw the installer on an error page:

22:06:48 - Analytics: response code 200 22:20:17 - Received WM_POWERBROADCAST with WPARAM 0xA LPARAM 0x0 01:40:39 - Received WM_POWERBROADCAST with WPARAM 0xA LPARAM 0x0 01:40:40 - Received WM_POWERBROADCAST with WPARAM 0x4 LPARAM 0x0 01:40:40 - Received PBT_APMSUSPEND so canceling the operation. 01:40:40 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:4174 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::CancelRunningOperation 01:40:40 - DownloadManager.cpp:439 DownloadManager::ClearExtraDownloadJobs 01:40:40 - CEndlessUsbToolDlg::CheckInternetConnectionThread cancel requested 01:40:40 - DownloadManager.cpp:452 Error calling EnumJobs. (GLE=[0]) 01:40:40 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:4155 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::EnableHibernate 01:40:40 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:1606 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::ChangePage 01:40:40 - ChangePage requested from ThankYouPage to ErrorPage

The spurious error page prompts our user to “Retry” the installation, which he dutifully does, despite the fact that nothing was actually ‘wrong’ in the first place. The installer at this point stumbles upon a much more pernicious bug – namely, it fails to check that Endless is not already installed before starting to install it again; it plows right ahead, deleting our C:\endless file and recreating it again (unnecessary, but not by itself problematic), and then goes to install GRUB. When it looks in the boot sector for the Windows MBR to copy out, it sees that the bootloader there is not in fact a Windows one – it’s something else, something strange and unexpected that it doesn’t know how to deal with, so it aborts the installation process and deletes the C:\endless it had just created:

08:02:50 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:5174 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::WriteMBRAndSBRToWinDrive 08:02:50 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:5320 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::GetPhysicalFromDriveLetter 08:02:50 - Opened drive \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE0 for write access 08:02:50 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:5134 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::IsWindowsMBR 08:02:50 - C:\ has a non-Windows MBR 08:02:50 - Error: no Windows MBR detected, unsupported configuration. 08:02:50 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:4993 Error on WriteMBRAndSBRToWinDrive (GLE=[87]) 08:02:50 - SetupDualBoot exited with error. 08:02:50 - EndlessUsbToolDlg.cpp:4698 CEndlessUsbToolDlg::RemoveNonEmptyDirectory 08:02:51 - Removing directory 'C:\endless\' result=0

The irony of course is that this ‘strange’ bootloader that our installer refuses to deal with is our GRUB installation that we put there in the first place! The computer is now, although still running, a dead man walking. Once you turn it off, it will never boot again, because it is stuck in limbo: it has a GRUB bootloader, but without the requisite C:\endless\endless.img file in place, GRUB can’t find the C: partition, and, hence, can’t find the rest of the code needed to complete the GRUB initialization process and boot into either Endless or Windows.

The Fix

As is often true with nasty, edge-case bugs like this one, the real work is in finding and reproducing it (and in that we were lucky to have the log file of a similarly affected machine). Once the nature of the problem is known, fixing it was quite straightforward. We cannot boot the machine from its internal disks, but we can boot from a USB. Once running on a ‘live’ Endless USB, we can do the repair work needed to get the system back into a coherent state. Concretely, we recreate the deleted C:\endless\ directory, and inside of it we put a blank endless.img file (so GRUB can find the partition) and a grub\ subdirectory (so GRUB can complete its execution). We can then power off the machine and remove the USB drive. Upon reboot, GRUB will now execute to completion and, since endless.img is just a blank file, will boot directly into Windows. From there we can run the uninstaller to clean everything out, then download a new version of the installer and do a proper install.

It is these two items, the endless.img file and the grub directory, that must be manually restored to the Windows partition in order for the computer to be bootable again.

The new version of the installer has two important fixes to ensure this error does not happen again. Firstly, it will not show a spurious error page when the application receives the suspend signal; secondly, it will ensure that the error code path includes a check for whether C:\endless is already installed before embarking on the install process all over again. Had that check been in place, the installer would never have deleted endless.img the second time round, thus avoiding that dreadful ‘half-way’ state. This problem was, therefore, one of those curious oddities in software development where you have two bugs layered on top of each other: a glaring, catastrophic one hidden in the code path of a subtle, marginal one.