Notwithstanding Brazil’s position as the seventh largest economy and fifth most populous nation on Earth, its political crisis of late has received relatively little attention in the foreign press – or, at least, in the American and British press I follow. Part of that is no doubt due to the fact that both countries are fixated on their own respective political dramas: the US its presidential election, and the UK its upcoming referendum on EU membership. Journalists and commentators have precious little ink to spare on the domestic turmoils of a ‘developing’ country, many thousands of miles away – not when they could be agonizing over the latest Trump or Farage gaffe for their readers.

The lack of attention is quite a shame though, since Brazil’s political crisis stands to affect many millions in the next several weeks, and has so far had all the intrigue of a House of Cards episode. The drama has been simmering for some months now, but this week things really came to a head. On Monday, a congressional committee voted 38-27 in favour of opening impeachment proceedings against the current president, Dilma Rousseff. On Friday (today!) that motion will go to the Congress at large, where they will begin debating it, and on Sunday a final vote will be taken. If two-thirds of the Congress vote in favour, Dilma will find herself impeached. That’s not quite the end of the road – she still has to endure the actual impeachment trial, and several more votes will be taken to determine whether she is guilty of whatever they are charging her with (more on that later), but given that the same people who vote to impeach her are probably going to end up finding her guilty, this Sunday is pretty much the Rubicon moment. But how did we get here?

Central to this crisis is a federal police investigation known as Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) – so named because it started with a discovery that certain Brazilian companies were using a car wash outfit as a front for money laundering. What started as a pretty run of the mill white collar crime investigation soon metastasized into a major political crisis, when it was discovered that these same companies involved in money laundering had also been handing out astronomical sums of money in the form of bribes to the country’s top politicians, in exchange for lucrative government contracts, principally at Petrobras, the giant, state-controlled oil company. The way such bribes might work is like this: Petrobras (i.e. the government) wants to build a new oil rig, so it approaches a construction contractor. Both contractor and politician know that a ‘fair’ price for the rig is, say, \$20 million. But instead, the contractor charges \$25 million, and ‘kicks back’ \$1 million of that to the politician by way of a secret channel. So the politician is up a million and the contractor up \$4 million (above the ‘fair’ price). Everybody wins. Except of course the poor taxpayer, who has overpaid by \$5 million. All of this is of course wholly illegal, not to mention grossly unethical. And yet the Lava Jato found out that it was happening with alarming frequency all across the nation’s capital. Indeed, the sheer size and extent of the corruption almost beggars belief. The latest estimate puts the total figure of laundered money at 10 billion reais (\$2.8 billion). The prosecution team, working out of its relatively unassuming offices in the southern city of Curitiba, has formally charged over 70 politicians and corporate executives with an assortment of crimes ranging from corruption to tax evasion. Some of these prosecutions have already run the full judicial gambit, resulting in top executives, such as Marcelo Odebrecht, being hauled off to jail – an unthinkable sight in the United States. Odebrecht, chief executive of his namesake construction company, will serve 19 years in prison for corruption charges.

Indeed, the rather bittersweet fact about the Lava Jato is that any dismay and disappointment an average citizen might have at seeing what gross misconduct is being uncovered is in a way offset by seeing with what vim and vigor the prosecution team is rounding up the culprits. For perhaps the first time in Brazil, the financial and political elite no longer seem to be above the law. Ordinary brazilians, who have long known that such corruption was afoot but felt nothing could be done about it, greet with barely contained Schadenfreude the photos of influential politicians and captains of industry being escorted into the back of police vans, just like a common favela thief. It is to the credit of the current government that the investigation is proceeding so smoothly and efficiently. Even when charges have been brought against members of their own party, the PT (Worker’s Party), the government has for the most part allowed the police and the prosecutors to do their job. Again, this is almost unheard of for Brazilian politics, and indeed for politics in general.

In fact, a big criticism some are beginning to raise about the Lava Jato is that perhaps it is being prosecuted a bit too eagerly. At times, people seem to be getting hauled off into custody without being given half a chance even to explain themselves. Such was the fate of former president Lula, whom prosecutors claim (based on somewhat dubious testimony of another convicted politician) is living in a house paid for with dirty money. Lula denies these charges, claiming they are mere smear tactics and warning that PT’s political opponents are orchestrating a coup against his the current government. Concerns that the Lava Jato team is running roughshod over basic legal tenets like presumption of innocence and habeas corpus, are not, as its defendants might claim, confined to just the Worker’s Party and its supporters. The respected British law firm, Blackstone, has pointed out that “if concerns that pre-trial detention is being used as a means to compel a detainee to become a state witness are well-founded such an approach would be inconsistent with international and comparative law norms and would be likely to place Brazil in breach of her obligations in international law.” So far, though, the prosecution team looks to be banking on the fact that public support to end systemic corruption is so high that they can continue casting their ambitiously wide net.

No matter how wide they cast that net however, the Lava Jato team have still not managed to ensnare their great white whale, namely President Rousseff herself. She is (so far) one of very few politicians who have not yet been connected to any criminal wrongdoing. That’s why, for many of Dilma’s supporters, the clamour for impeachment comes across as a sort of bizarre non sequitur. The impeachment charge against Dilma is that she and her administration manipulated the public accounts just prior to the last election in order to artificially understate the true size of the government’s debt liability. Even if irrefutable evidence were presented to back this claim, it is not at all clear that it is an impeachable offence – for one, Brazil’s constitution rules that a president can only be impeached for crimes committed during the current term, and this alleged cooking of the books would have happened in her previous term. More importantly, however, Dilma’s impeachment charge has nothing to do with the ‘kickback’ scheme being investigated by Lava Jato. It is easy to miss that important fact, not least because virtually all the media outfits in the country, controlled and owned by a few extremely wealthy families, which often don’t even attempt to hide their open hostility to the Dilma government, have tended to lump both the Lava Jato case and the impeachment proceedings under the general heading of unscrupulous governance.

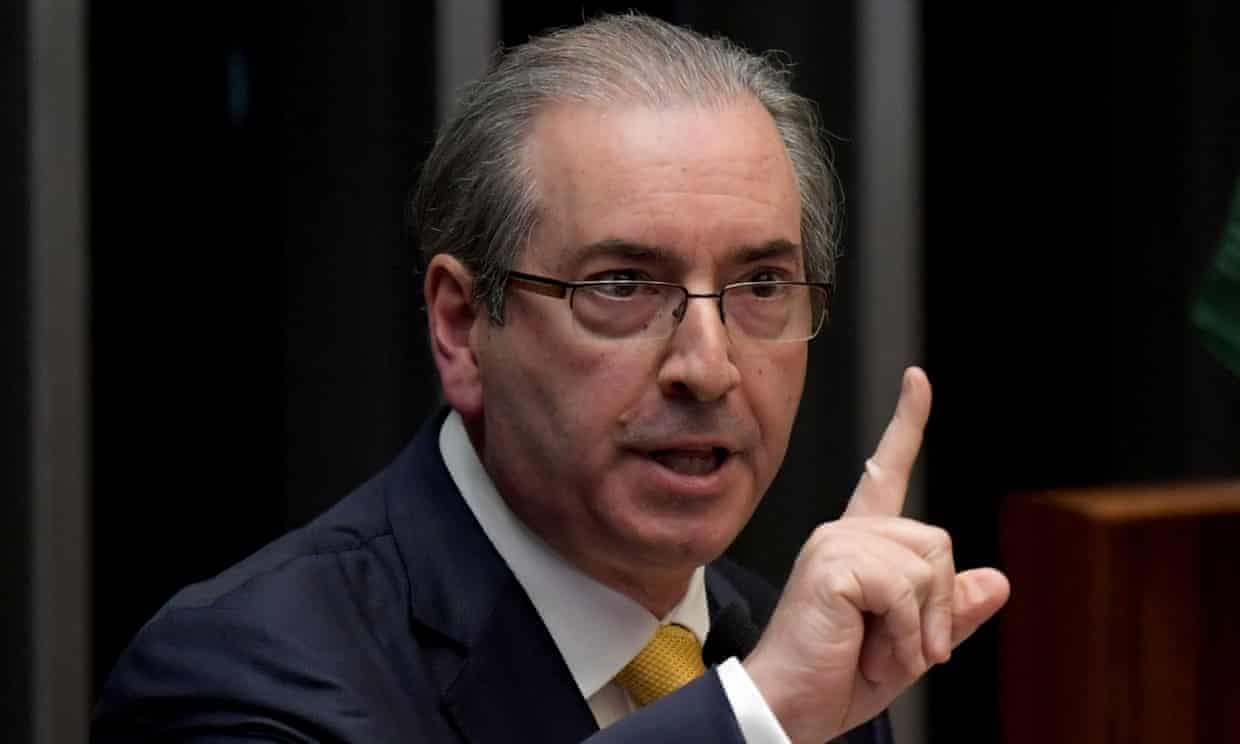

The man leading the impeachment charge is a one Eduardo Cunha, a self-professed Evangelical politician, who has spent much of his career pushing to restrict women’s reproductive rights and to make society increasingly unwelcoming towards homosexuals. The political climate since the last election has been marked by open acrimony between the president and Cunha, who has frustrated any and all efforts to pass legislation she tries to bring forward, even to support the ailing economy. The comparison to Boehner and Obama circa 2010 is not without merit. As Speaker of the House, Cunha can decide which legislation to bring forward to a vote, and he simply blocks measures his party does not agree with. One bill he did put forward this session was a proposal to lower the age of criminal responsibility from 18 to 16 years old, a move which would have consigned many vulnerable youths to Brazil’s overcrowded and often very dangerous prisons. Unsurprisingly, many students and favela inhabitants fervently opposed this measure, and it did not end up passing. Cunha also happens to be one of 70 politicians involved in the Lava Jato corruption scandal – prosecutors found evidence of him squirreling away a cool $5 million in illicit funds in a Swiss bank account. The hypocrisy of Cunha calling Dilma unfit for political office when it is he who has been indicted for corruption and not her is almost laughable. It is also worth pointing out that were both Dilma and her vice president, Michel Temer, to fall, it is Cunha who would assume the presidency, as per the constitution, and no doubt this factors into his calculus.

Another rather colorful character worth mentioning in this saga is Jair Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro is a hateful, bigot of a man whose personal antics make Donald Trump look like a bleeding heart liberal. He once told a fellow female politician that she was “not worthy of being raped”, and made international headlines when, in an interview with Stephen Fry, he remarked that “no father would ever take pride in having a gay son.” Perhaps even more frightening than these disgusting slurs, Bolsonaro openly defends the past military dictatorship, despite recent revelations that it engaged in widespread torture and extrajudicial killings. I mention him here not just because he is an easy target for whipping up leftist vitriol, but because in the last general election, he received the most votes – 464,000 – out of any congressman in the country. He has also put his name forward as a potential candidate for the next presidential election. In other words, given that the PT will have fallen into disgrace, there is serious worry among leftists that Bolsonaro – or someone like him – will come to power. Whatever criticisms one might have about the PT, there’s no denying that in their decade in office under Lula, they were able to lift literally tens of millions of Brazilians out of poverty and provide educational opportunities to those who before had never dreamed of such things. There is a real fear among progressives in Brazil that whoever succeeds Dilma will seek to reverse all of this by dismantling the social programs and safeguards put in place to help working families. Many maintain that right-wing forces are hijacking the current disgust at politicians and at government in general in order to push their own ideological agenda.

Of course, it is absurd and unfair to suggest that everyone supporting the impeachment is some kind of right-wing saboteur. Most are just normal, everyday Brazilians who are simply sick and tired of the endemic corruption in their country and want something to be done about it. For them, this is their one moment to overhaul the system for good, and just completely clean house. The corruption we have in the US, prevalent as it is, rarely affects the day to day life of the average citizen (which, in a way, makes it more pernicious and more difficult to weed out). The same is not true in Brazil. Brazilians encounter corruption when they apply for a driver’s license and find out that if you’re chums with the transport secretary your application can be whisked along; if not it can take years. They encounter it when they get stopped by the police, and find out that an under the table bribe of 200 reais to the cop can mean the difference between points on your record or not. They encounter it when they try to start a business, and have to jump through all sorts of Kafka-esque hoops and hurdles just to do something simple like open an office. They are fed up with reading that the full economic might of their country is being held back by incompetent and dishonest politicians. But despite these genuine grievances, the truth is that corruption did not start with Dilma and the PT, and there is little reason to think it will end with them either.